Disc herniations in the neck can cause severe, debilitating pain, restrict the range of motion of the neck, and cause nerve symptoms such as burning, tingling, or weakness down the upper back, shoulders, arms, forearms, wrists, and hands. The pain and dysfunction experienced from a herniated disc in the neck is explained below:

- Nociceptive pain – This means that pain is being triggered from the herniated disc and the affected surrounding muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints.

- Referred pain – Usually a deep gnawing, aching, expanding pain with difficult to define borders and an easier to define “core/center”. This can occur because of shared innervation (nerve connections) between the disc herniation and healthy uninjured tissues.

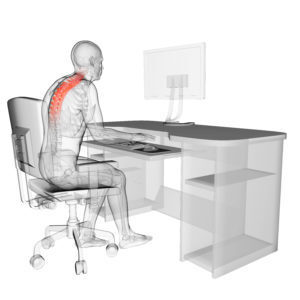

Radicular pain – When a disc herniates, it can cause inflammation and/or compression of a specific nerve root in the adjacent vicinity. This will cause a distinct pattern of pain or dysfunction in what is known as a dermatomal distribution, pictured below (marked with C2-T1):

Radicular pain – When a disc herniates, it can cause inflammation and/or compression of a specific nerve root in the adjacent vicinity. This will cause a distinct pattern of pain or dysfunction in what is known as a dermatomal distribution, pictured below (marked with C2-T1):

- Radiculopathy – This is not defined by pain, but by nerve symptoms. This is caused by blocked nerve impulses at the level of the herniated disc in the neck. It is defined by sensation loss in the form of numbness/tingling and by motor loss in the form of weakness. This also follows a dermatomal distribution as the one shown above (marked C2-T1). Often times, radicular pain and radiculopathy will be seen together.

The recommended first line of defense for disc herniations is conservative care (Wong et. al. 2014). In our office, this is usually a combination of manual treatments to the neck and its surrounding region, as well as specific therapeutic exercises. This joint venture between the treating provider and the patient, has consistently shown good outcomes. In Wong’s et. al systematic review of the current literature, most cases of neck disc herniations recover and do not require surgery even when radiculopathy is originally present.

It was also found, after a systematic review of 1,221 research articles, that the most significant improvement was seen 4-6 months after the initial onset of pain and that complete recovery was 24-36 months post initial onset (Wong et. al. 2014). However, in our office, using a blind internal questionnaire of 32 cases, we averaged a 73.6% subjective improvement reported at the 30 day mark from the start of treatment. This is remarkable when compared to the current literature.

If you or someone you know is suffering from a disc herniation of the neck, we’re here to help!

References

Bogduk, Nikolai. “On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain.” Pain147.1 (2009): 17-19. Web.

Lee, M.w.l., R.w. Mcphee, and M.d. Stringer. “An evidence‐based approach to human dermatomes.” Clinical Anatomy21.5 (2008): 363-73. Web.

“Magnetic resonance imaging in the follow up of patients operated on for aortic dissection (in Italian).” Clinical Imaging18.4 (1994): 292. Web.

Souter, Andrew. “Anatomy and pathophysiology of back pain.” OPML Back Pain(2012): 19-28. Web.

Wong, Jessica J., Pierre Côté, Jairus J. Quesnele, Paula J. Stern, and Silvano A. Mior. “The course and prognostic factors of symptomatic cervical disc herniation with radiculopathy: a systematic review of the literature.” The Spine Journal14.8 (2014): 1781-789. Web.